Hrdy considers how Humans evolved their large brain size and prolonged childhood. She suggests a key factor was that Hominins were cooperative breeders as are 9% of bird species, generally those which are non-migratory, and 3% of mammals. Australian fairy-wren females are attracted to a male with its own territory. They are joined by up to three younger males often sons of the breeding female which surreptitiously mates with other males.

Cooperative breeding applies to any species which provides alloparental care and provisioning by those who are not direct parents. Other Hominids including the Great Apes are not communal breeders. Their females generally move away from the group. Infants are in continual contact with their mothers for 5 to 6 months and nursed for 4 to 7 years. Mothers are unwilling to let others touch their infant, This is likely to be because of the high incidence of infanticide.

This care and contact model was adopted in the attachment theory for the nurturing of human infants. Hrdy however instead stresses the importance of alloparental assistance in carrying and providing for young children. She thinks that cooperative care may be ancient, possibly dating to when hominins lost body hair 3.3 m years ago, so infants could no longer clinge to body hair; the change recorded by the lice that lived in fur being replaced by those in pubic hair. The change may also be reflected in the way children are born with the grasping reflex, which was used to cling to a hair covered mother, but which human babies lose within six months. Hrdy suggests that cooperative breeding facilitated humans becoming prosocial, under the theory of the mind infants becoming conscious of self and intuitive to their interaction with others, intersubjectivity then developing further with the adoption of language. Rather than societal complexity driving humans to become prosocial, Hrdy argues cooperative breeding drove hominins to become pro-social with the result that society could develop to be more complex.

Infants become increasingly sophisticated in knowing what attracts attention. They babble while mothers talk motherese. Hrdy suggests this developed in hunter-gatherer societies where babies are never left alone and babble and motherese ensured contact both between mother and child and between the chid and alloparents. By contrast chimps do not babble, are self-regarding and uncooperative, similar to autistic humans.

100,000 years before present there may have been as few as 10,000 anatomically modern Homo sapien breeding adults. 50/70,000 years ago threatened with extimction,they may not have survived. The chimp genome is more diverse than that of humans, suggesting they are descended from a more diverse and numerous founding stock.

Hunter-gatherer societies divided roles between male hunters and women gatherers. The !Kung and Akai are both characterised by affectionate fathers. !Kung fathers hold their children 2% of the time, the Akai for ten times this. Some of this was environmentally driven and culturally adapted, the !!Kung living in the desert and semi-desert, the Akai in the forests hunting with nets and taking their children with them.

Under the grandmother hypothesis grandmothers surviving after the menopause continued gathering and supported their daughters. Alternatively siblings, particularly girls, are involved in alloparental care. Under the grandfather hypothesis older wise men kept groups together. However they restricted the marriage options of younger men. monopolising younger women.

Hunter-gatherers are equalitarian and avoided conflict. Gift giving is deeply rooted based on nature being thought of as giving. Sharing ensured survival. To spread the potential support net wider their relationships were traced through both mother and father. Polyandry was common reducing the risk of depending on a single father and with the possibility that both husbands might believe they were a child’s father reducing the risk of infanticide.

Generally child well-being was better were families were matrilocal, living with a mother’s parents. Australian aborigines were traditionally patrilocal with polygamy favouring male reproduction, but at the price of the wellbeing of children. In the Arnhem Land child survival was higher where wives were related. In one group 68% of polygamous married women were sisters.

With the Neolithic society became more sedentary, settlements nucleated for defence, so sons stayed with fathers and brothers and descent became patriarchal. Female chastity and the perpetuation of the male line were emphasised and without the mother’s family the health of both mothers and children deteriorated, sequestration and suttee harming them and discouraging paternal care.

Intervals between births was reduced for the privileged through the use of wet-nurses whose own children were likely to be neglected with further births to the wet nurse delayed by feeding the offspring of the privileged. A caste of eunuchs guarded women. Hrdy doesn’t cover it, but you are left wondering how celibate monks, nuns and priests fitted into this pattern.

Europeans were amazed by the openness and generosity of hunter-gatherers. This left them susceptible to exploitation by aggressive and stratified societies with technically advanced weapons and ships.

Over Human lives family structures and localities change. Hrdy sees this in the nuclear “normal” family being a recent phenomenon and even then only a temporary phase in an individual’s life.

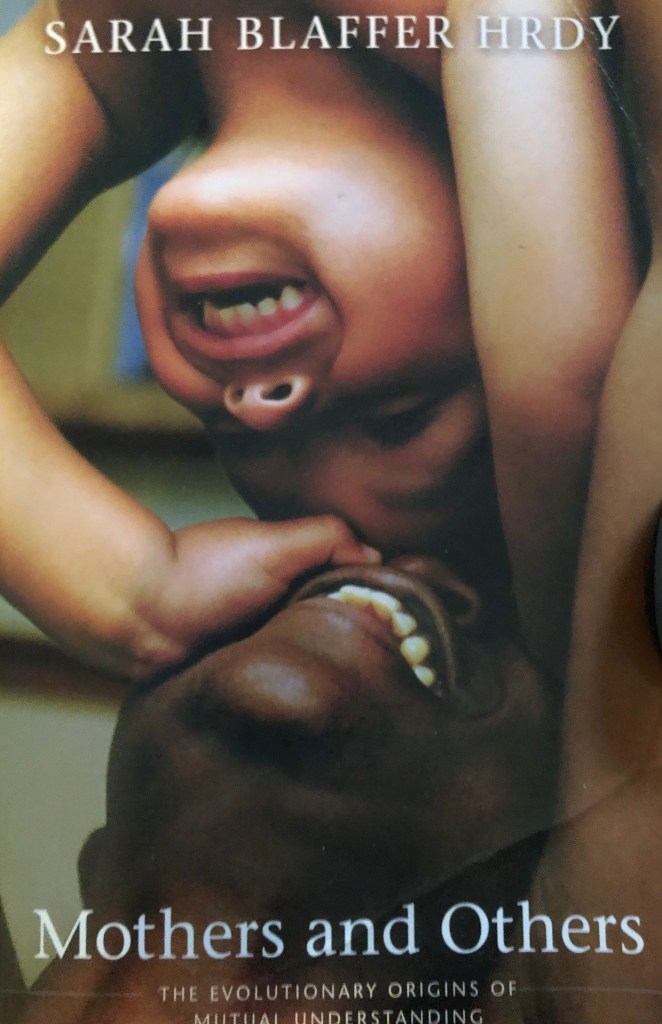

This is a book with wide scope, which makes interesting points. However, it comes across as a reference work, a series of separate ideas where editing might have produced a clearer thread. There are great photographs illustrative of the text, but they were often blurred in the paperback.